E-Democracy,

E-Governance and Public Net-Work

By Steven Clift

http://www.publicus.net

Copyright 2003 - Permission

required for print or electronic redistribution.

Version 1.1, September 2003

My Related Articles:

Introduction

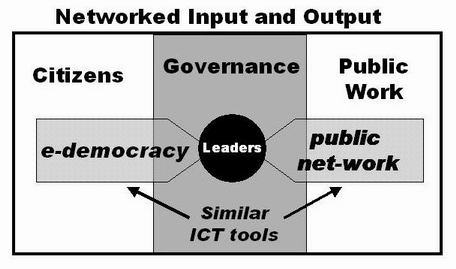

While the art and practice of government

policy-making, citizen participation, and public work is quite complex,

the following illustration provides a simple framework used in this paper:

In this model of traditional government

policy-making:

1. Citizens provide occasional

input between elections and pay taxes.

2. Power in the Governance infrastructure

is centered with political leaders who determine broad policy priorities

and distribute resources based on those priorities and existing programs

and legal requirements.

3. Through government directly, and other

publicly funded organizations, Public Work represents the implementation

of the policy agenda and law.

Over time of course, bureaucratic barriers

to reform make it difficult for leaders to recognize changes in citizen

needs and priorities. Citizen input, outside of elections, often

has a difficult time getting through. Disconnects among citizens,

leaders, and those who implement public work are often based on the inability

to easily communicate through and across these groups.

As our one-way broadcast world becomes

increasingly two-way, will the governance process gain the ability to listen

and respond more effectively?

The information-age, led by Internet content,

software, technology, and connectivity, is changing society and the way

we can best meet public challenges. E-democracy, e-governance, and public

net-work are three interrelated concepts that will help us map out our

opportunity to more effectively participate, govern, and do public work.

E-Democracy

E-democracy is a term that elicits a wide

range of reactions. Is it part of an inevitable technology driven revolution?

Will it bring about direct voting on every issue under the sun via the

Internet? Is this just a lot of hype? And so on. (The answers … no,

no, and no.)

Just as there are many different definitions

of democracy and many more operating practices, e-democracy as a concept

is easily lost in the clouds. Developing a practical definition of

E-Democracy is essential to help us sustain and adapt everyday representative

democratic governance in the information age.

Definition

After a decade of involvement in this field,

I have established the following working definition:

E-Democracy is the use of information and

communications technologies and strategies by “democratic sectors” within

the political processes of local communities, states/regions, nations and

on the global stage.

The “democratic sectors” include the following

democratic actors:

-

Governments

-

Elected officials

-

Media (and major online Portals)

-

Political parties and interest groups

-

Civil society organizations

-

International governmental organizations

-

Citizens/voters

Current E-Democracy Activities

Each sector often views its new online

developments in isolation. They are relatively unaware of the

online activities of the other sectors. Those working to use information

and communication technologies (ICTs) to improve or enhance democratic

practices are finding e-democracy a lot more challenging to implement than

speculating on its potential. This is why it is essential for the

best e-democracy lessons and practices to be documented and shared.

This simplified model illustrates e-democracy

activities as a whole. Building on the first diagram it, sits

as a filter on the “input” border between citizens and governance in first

diagram:

Governments provide extensive access to

information and interact electronically with citizens, political groups

run online advocacy campaigns and political parties campaign online, and

the media and portal/search sites play a crucial role in providing news

and online navigation. In this model, the “Private Sector” represents

commercially driven connectivity, software, and technology. This

is the whole of e-democracy.

E-democracy is not evolving in a vacuum

with these sectors only. Technology enhancements and online trends

from all corners of the Internet are continuously being adopted and adapted

for political and governance purposes. This is one of the more exciting

opportunities as e-mail, wireless networking, personalization, weblogs,

and other tools move in from other online content, commerce, and technology

areas and bring innovation and the opportunity for change with them.

Looking to the center of model, the only

ones who experience “e-democracy” as a whole are “citizens.”

In more “wired” countries most citizens are experiencing information-age

democracy as “e-citizens” at some level of governance and public life.

In developing countries, e-democracy is just as important, but exists as

more of an institution-to-institution relationship. In all countries,

the influence of “e-democracy” actually reaches most of the public through

its influence on the traditional media and through word of mouth via influential

members of the community.

“E-Citizens” - Greater Citizen Participation?

To many, e-democracy suggests greater and

more active citizen participation enabled by the Internet, mobile communications,

and other technologies in today’s representative democracy. It also

suggests a different role for government and more participatory forms of

direct citizen involvement in efforts to address public challenges. (Think

e-volunteerism over e-voting.)

Some take this further and view the information

revolution as an inherently democratic “disruptive technology” that will

dramatically change politics for the better. This view has diminished

considerably, as existing democratic actors have demonstrated their ability

to incorporate new technologies and online communication strategies into

their own activities and protect their existing interests. They have

to in order to survive.

In the future, most “e-democracy” development

will naturally result from ICT-accelerated competition among the various

political forces in society. We are experiencing a dramatic “e-democracy

evolution.” In this evolution, the role, interests, and the

current and future activities of all actors is not yet well understood.

There is still an opportunity to influence its development for the better.

Things will change, but as each democratic

sector advances their online activities, democratic intent will be required

to achieve the greater goals of democracy.

Related resources:

E-Democracy

Resource Links

Future

of E-Democracy - The Fifty Year Plan

E-Democracy

E-Book: Democracy is Online 2.0

E-Governance

I use the phrase “Representative E-Government”

to describe the e-democracy activities of government institutions. Others

call this “e-governance.” Whether a local government or a United Nations

agency, government institutions are making significant investments in the

use of ICTs in their work. They are expressing “democratic intent.”

Their efforts make this one of the most dynamic and important areas of

e-democracy development.

There are distinct differences in how representative

institutions and elected officials use ICTs compared to administrative

agencies and departments. The use of ICTs by parliaments, heads of

state/government, and local councils (and elected officials in these institutions)

lags significantly behind the administrative-based e-government service

and portal efforts. This is a services first, democracy later approach.

This focus of e-government resources on

services does not mean that e-democracy is not gaining increased attention

in some governments. In fact, leading e-service governments are now

at a point where they are exploring their e-democracy responsibilities

more seriously.

Goals for E-Democracy in Governance

Investment in traditional e-government

service delivery is justified based on the provision of greater citizen

convenience and the often-elusive goal of cost-savings. Goals for

e-government in governance that promote democracy and effective governance

include:

1. Improved government decisions

2. Increased citizen trust in government

3. Increased government accountability

and transparency

4. Ability to accommodate the public will

in the information-age

5. To effectively involve stakeholders,

including NGOs, business, and interested citizen in new ways of meeting

public challenges (see public net-work below)

Consultation Online

The first area of government e-democracy

exploration has focused on consultation within executive policy-making

processes. Governments, like the United Kingdom and Canada, are taking

their consultative frameworks and adapting them to the online environment.

New Zealand and Canada now have special portals dedicated to promote the

open consultations across their governments. This includes traditional

off-line opportunities as well as those where online input is encouraged.

Across the UK, a number of “online consultations” have been deployed to

gather special citizen input via the Internet.

Examples:

Consulting Canadians: http://www.consultingcanadians.gc.ca

New Zealand – Participate: http://www.govt.nz/en/participate

UK E-Democracy Consultation: http://www.e-democracy.gov.uk

Others, including hosting and best practice

tips: http://www.publicus.net/articles/consult.html

Accountability, Trust, the Public

Will

These three themes are emerging on the

e-democracy agenda. Building government accountability and transparency

are a significant focus of e-government in many developing countries.

E-government is viewed an anti-corruption tool in places like South Korea,

Mexico, and others. Trust, while an important goal, can only be measured

in the abstract. Establishing a causal relationship between e-government/e-democracy

experiences and increased levels of trust will be difficult.

Ultimately, the main challenge for governance

in the information age will be accommodating the will of the people in

many small and large ways online. The great unknown is whether citizen

and political institutional use of this new medium will lead to more responsive

government or whether the noise generated by competing interests online

will make governance more difficult. It is possible that current

use of ICTs in government and politics, which are often not formulated

with democratic intent, will actually make governance less responsive.

One thing is clear, the Internet can be

used to effectively organize protests and to support specific advocacy

causes. Whether it was the use of e-mail

groups and text messaging protesting former President Estrada of the Philippines

or

the fact a majority of Americans online sent

or received e-mail (mostly humor) after the Presidential election “tie”

in the United States, major moments in history lead to an explosion

of online activity. The social networks online are very dynamic and governments

need to be prepared to accommodate and react to “electric floods.” When

something happens that causes a flood, people will expect government to

engage them via this medium or citizens will instead view government as

increasingly unresponsive and disconnected with society they are to serve.

Related resources:

For more on the e-government and democracy,

watch for the 2003

United Nations World Public Sector Report. Details will be shared on

DoWire: http://www.e-democracy.org/do

Top

Ten E-Democracy "To Do List" for Governments Around the World

Top

Ten Tips for "Weos" - Wired Elected Officials

Public Net-Work

Public net-work is a new concept. It represents

the strategic use of ICTs to better implement established public policy

goals and programs through direct and diverse stakeholder involvement online.

If e-democracy in government represents

input into governance, then public net-work represents participative output

using the same or similar online tools. Public net-work is a selective,

yet public, approach that uses two-way online information exchange to carry

out previously determined government policy.

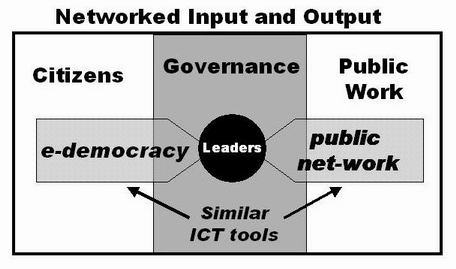

Building on the first diagram, the following

“bow-tie” model suggests a more fluid communication environment that can

be used to bring citizens and public work stakeholders closer to the center

of governance. It also suggests that policy leaders can reach out

and develop closer relationships with citizens and stakeholders.

What are public net-work projects?

Public net-work projects have the following

things in common:

1. They are designed to facilitate

the online exchange of information, knowledge and/or experience among those

doing similar public work.

2. They are hosted or funded by government

agencies, intergovernmental associations, international government bodies,

partnerships involving many public entities, non-governmental organizations,

and sometimes foundations or companies.

3. While they are generally open to the

public, they are focused on specific issues that attract niche stakeholder

involvement from other government agencies, local governments, non-governmental

organizations, and interested citizens. Essentially any individual

or group willing to work with the government to meet public challenges

may be included. However, invite-only initiatives with a broader base of

participants are very similar to more strictly defined “open” public net-work

initiatives.

4. In a time of scare resources, public

net-work is designed to help governments more effectively pursue their

established missions in a collaborative and sustainable manner.

In order to work, public net-work initiative

hosts need to shift from the role of “top experts” or “sole providers”

of public services to facilitators of those working to solve similar public

problems. Public net-work moves beyond “one-way” information and

service delivery toward “two-way” and “many-to-many” exchange of information,

knowledge, and experience.

Features

Publicly accessible public net-work projects

currently use a mix of ICT tools available. The successful projects

adopt new technologies and strategies on an incremental trial and error

basis. Unleashing all of the latest tools and techniques without a user

base may actually reduce project momentum and user participation.

To succeed, these projects must adapt emerging

models of distributed information input and information sharing and develop

models for sustained knowledge exchange/discussion. They must also

build from the existing knowledge about online communities, virtual libraries,

e-newsletters, and Communities of Practice/Interest.

Some of the specific online features include:

1. Topical Portal - The starting

point for public net-work is a web site that provides users a directory

to relevant information resources in their field - these often include

annotated subject guide links and/or standard Yahoo-style categories.

2. E-mail Newsletter - Most projects keep

people up-to-date via regularly produced e-mail newsletters. This human

edited form of communication is essential to draw people back to the site

and can be used to foster a form of high value interaction that helps people

feel like they are part of the effort.

3. Personalization with E-mail Notification

- Some sites allow users to create personal settings that track and notify

them about new online resources of interest. New resources and links to

external information are often placed deep within an overall site and "What's

New" notification dramatically increases the value provided by the project

to its users.

4. Event Calendar - Many sites are a reliable

place to discover listings of key current events and conferences.

5. FAQ and Question Exchange - A list of

answers to frequently asked questions as well as the regular solicitation

of new or timely questions from participants. Answers are then gathered

from other participants and shared with all via the web site and/or e-newsletter.

6. Document Library - Some sites move beyond

the portal directory function and gather the full text of documents. This

provides a reliable long-term source of quality content that often appears

and is removed from other web sites without notice.

7. Discussions - Using a mix of e-mail

lists and/or web forums, these sites encourage ongoing and informal information

exchange. This is where the "life" of the public net-work online

community is often expressed.

8. Other features include news headline

links from outside sources, a member directory, and real-time online features.

Examples

CommunityBuilders New South Wales – http://www.communitybuilders.nsw.gov.au

International AIDS Economics Network – http://www.iaen.org

OneFish – http://www.onefish.org

DevelopmentGateway – http://www.developmentgateway.org

Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry

- Digital New Deal - http://dnd.rieti.go.jp

UK Improvement and Development Agency – Knowledge

– http://www.idea-knowledge.gov.uk

Lessons

1. Government partnerships, with

their public missions and resources, often make ideal hosts for broad,

horizontal information exchange. Government departments that feel

their status/purpose will be threatened by shifting from an expert gatekeeper

to an involved facilitator are not ideal hosts.

2. All online features must be designed

with the end user in mind. They must be usable and easy to learn.

Complex systems reduce the size of the participatory audience – public

net-work cannot rely on an internal office environment where people are

required to learn new systems or use specialty software beyond e-mail and

a web browser. To provide a strong incentive, these systems must save the

time it takes those implementing public policy to do their job effectively.

3. Public net-work sites broaden the awareness

of quality information resources on a timely basis. Finding what

you need, when you need it is more likely to occur when a community of

interest participates in building a comprehensive resource. However,

over time these sites will naturally face currency issues that must be

handled. There are limits to the value of information exchange. Too

much information, or bad information, can paralyze decision-making or distract

people from the task at hand. All good things should be taken in

moderation.

4. Building trust among the organizations

and individuals participating in the development and everyday use of a

collaborative site is essential. This relates to developing the “neutral

host” facilitation role, along with sustained funding, by the host.

Special care must be taken when building partner relationships and host

“branding” kept to a minimum. Partnerships, with clear responsibilities

and goals, will better position efforts as a truly participatory community

projects.

5. Gathering and sharing incentives, particularly

for resource links is a particularly tricky area. Involving people

with solid librarianship and communication skill sets is essential.

Creating a more sustainable model where participants more actively submit

information (e.g. seeking submissions from users for more than 5% of link

listings for example) is an ongoing challenge. In-kind partnerships where

staff time is donated may be more effective than relying on the time of

unaffiliated individual volunteers. With more localized efforts,

individual volunteers may be the best or only option.

6. Informal information sharing has tremendous

potential. To effectively encourage horizontal communication, facilitation

is often required. Projects must leverage existing online communities and

be willing to use technologies, like e-mail lists if that is what people

will actually use. In my opinion, the CommunityBuilder.NSW site is

one of the few sites that effectively integrate e-mail and web technology

to support sustained online deliberation and information exchange.

7. The connection to decision-makers and

authority is significant. Government-led public net-work projects

require political leadership and strong management support. Paradoxically,

an effective online involvement program on the implementation side of government,

if connected to government leaders, may operate as an “early warning system”

and allow government to adapt policy with fewer political challenges.

Related resources:

The public net-work section above

is based on an article I wrote for the OECD's E-Government Working Group.

An expanded discussion of case examples and the future direction of public

net-work is available in Public

Net-work: Online Information Exchange in the Pursuit of Public Service

Goals (Word/RTF).

Conclusion

To be involved in defining the future of

democracy, governance and public work at the dawn of the information-age

is an incredible opportunity and responsibility. With the intelligent and

effective application of ICTs, combined with democratic intent, we can

make governments more responsive, we can connect citizens to effectively

meet public challenges, and ultimately, we can build a more sustainable

future for the benefit of the whole of society and world in which we live.

This article originally prepared for ACP

FMKES Workshop: http://www.onefish.org/id/159181

PowerPoint presentation available from

(7MB): http://www.onefish.org/id/159425

To arrange a presentation or speech on

“public net-work” please contact Steven Clift and visit this web page for

more information: http://www.publicus.net/speaker.html

For more information about an online exchange

among leading public net-work practitioners, see: http://www.publicus.net/publicnetwork.html